This is the story of the broken heart of a man, the rusty heart of a city, and how they got all tangled up as one. Like a lot of us, he learned hope and heartbreak first from a baseball team, then from bruising bouts with love, then from the city in which he lived, but unlike a lot of us, he never learned to play along, never stopped seeing the way things are contrasted against the way things ought to be, never stopped championing the nobodies nobody knows—for there, he wrote, beats Chicago’s heart. He followed his own beat straight to the place where pride will lead you every time—to poverty and exile—while describing Chicago as no one had since Carl Sandburg and as no one has again. And save for the devotion of a peculiar few, the City of Big Shoulders shrugged him off.

This is the story of the broken heart of a man, the rusty heart of a city, and how they got all tangled up as one. Like a lot of us, he learned hope and heartbreak first from a baseball team, then from bruising bouts with love, then from the city in which he lived, but unlike a lot of us, he never learned to play along, never stopped seeing the way things are contrasted against the way things ought to be, never stopped championing the nobodies nobody knows—for there, he wrote, beats Chicago’s heart. He followed his own beat straight to the place where pride will lead you every time—to poverty and exile—while describing Chicago as no one had since Carl Sandburg and as no one has again. And save for the devotion of a peculiar few, the City of Big Shoulders shrugged him off.

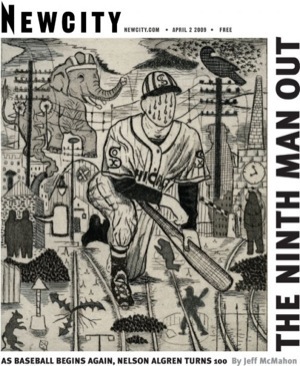

Maybe that’s changing. This spring, in readings and screenings and lectures, Chicago is noticing the 100th birthday of Nelson Algren, the writer who cast its heart in prose. Young Chicago writers are reaching for the tails of his Salvation Army coat, and old New York writers are flying into O’Hare—some Californians, too—to help Chicago toast his awakening memory.

There’s a wave building: In 2003, a panel on Algren was attended by five panelists and one audience member—who had come hoping to learn something about Algren’s lover, Simone de Beauvoir. This February, a similar panel drew eleven. In March, a Columbia College tribute attracted 150. And hundreds are expected to fill the Steppenwolf Theater for a reading of his works April 6. Whenever these events occur, the panelists marvel at Algren’s early brilliance and wonder at his devastating decline—for he began as the poet of the slums and became merely a resident therein. Mostly, Chicago seems sorry it didn’t appreciate Algren more when he was here.

Fifty years ago, when Algren’s books could be found in all the great cities of Europe, they could not be found in the Chicago Public Library. Fifty years ago, when commies couldn’t get passports, Algren couldn’t visit his books in Europe either, and while J. Edgar Hoover had him roped, the leading critics jabbed his “proletarian” interest in the downtrodden and his “sentimental” politics.

Fifty years ago, when he was 50, Nelson Algren was peddling book reviews to buy his bread, but he had not quite renounced hope, for as the September sun flew by on the wind, the White Sox finished first in the American League. The Sox had not visited a World Series since 1919, when eight players allegedly took bribes to throw the series. Algren was 10 in 1919 and living near 71st Street and Cottage Grove, in the shadow of the high cross of St. Columbanus. The Black Sox lured young Algren in, then let him down deeper than where he started, establishing the pattern of hope and heartbreak that echoed through his life, with wives and girlfriends, with literary fortune, with the city of Chicago. For the whole town, he wrote, is a rigged ball game. Despite such convincing grounds for heartbreak, for a few days in October of 1959, he gave hope another chance. The White Sox were returning to the World Series hungry for redemption, and so was Nelson Algren.

Algren wrote a column on each of the three home games—a towering win and two losses—for the Chicago Sun-Times. He recast the columns as an essay for his 1973 book, “The Last Carousel,” but the essay reads like it was revised with scissors and Scotch tape. It lacks the sincerity of the columns, written on deadline as hope turned again to heartbreak. Like an image of the Virgin in a highway underpass, Algren’s life reveals itself in this small series of columns: moments of brilliance, moments of bitterness, an unerring eye for what it means to be Chicagoan.

“I sent a half-dollar down the line to the vendor, never expecting to see any change and only half expecting a beer. It came back full after passing through 14 pairs of hands, and I thought that either we are getting considerate of our fellow man in Chicago or else we’re going soft.”

Algren devotes a lot of ink to his fellow man in the bleachers—and to a few unlucky women. The Sun-Times had its whole staff on the games, plus a guest column by an expert—White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox—so Algren, the novelist, was there to supply meaning. He primes the canvas with his own boyish hope, spinning us back four decades to a day when the Black Sox were still the White Sox and Babe Ruth had come to town chasing the single-season homerun record:

“Outside Sox Park, mounted police were trying to keep a mob of locked-out fans from crashing the centerfield fence, which was then wooden. Inside, Eddie Cicotte was pitching to Ruth. The crush of the mob swept police, horses, and myself onto the field, and I scampered into the centerfield bleachers. I’ve been in the centerfield bleachers ever since. The papers described the incident as RIOT AT SOX PARK! Overnight I became the kid who not only had survived a riot but had seen Cicotte strike out Ruth.”

As he brings us back to 1959, Algren describes “a great rising feeling.” The White Sox take the lead in Game One, and that lead grows to 11-0 by the time Algren leaves the park, without explanation, midway through the seventh inning. Although a second game had yet to be played, he writes a strangely prescient sentence in his first column: “Then the big Chicago afternoon light came down like the light of no other city, and I knew I would not see the White Sox like this again.”

In fact, Chicago would not see another home victory in the World Series until October 22, 2005.

When the White Sox lose the series in Game Six, Algren keeps to his seat while the fans clear out. It begins to rain. And then he does what he does whenever Chicago lets him down—it’s what he does best: he evokes the silver-colored yesterday, which is not so much a past Chicago as a parallel Chicago, a Chicago where Cicotte always strikes out Ruth. Thirty years before “Field of Dreams,” Algren sees ghosts practicing on the infield:

“I have seen the hep-ghosts of the rain before. I know who they are. They are ghosts of old-time buskers and long-gone hustlers that have been left here and there around town for haunting of bars and ball parks, to play make-believe World Series there after the squares have gone home…. I have seen the ghosts of blue-moon hustlers leaping drunk below the all-night billboard lights. Yesterday evening, when the crowd was gone and I stood up at last to leave, I saw the shade of Shoeless Joe. He was walking toward the darkening stands, and he’d left his glove behind.”

Between hope and heartbreak, many innings, many strikes, many balls, but Algren has trouble concentrating. There’s a woman sitting near him at each game, saying something he can’t ignore. Married three times on paper and once in spirit, Algren was troubled by women at home, too—especially by Simone de Beauvoir.

In Game One, White Sox pitcher Early Wynn hits a double in the third, and a ball boy runs out to give him his jacket—a precaution to keep the pitcher’s arm from getting cold. Algren overhears a woman asking, “Aren’t they going to play it out?” She thought Wynn was dressing to go home. Later, the woman asks her husband the score, and he tells her it’s 11-0 in the fourth. Algren writes: “I actually heard her ask, ‘Does that mean it will be 22-0 in the eighth?’”

In Game Two, Senator John F. Kennedy is sitting beside the mayor in the Daley Family box, while in the bleachers a woman “just showing the first signs of mileage” sits beside Algren. She’s wearing blue corduroy. She doesn’t care much for baseball, but Algren tells her what’s going to happen before it happens: “I told Blue Corduroy, ‘He’s going to hit,’ and the crack of that bat came so solid I stood up to see if I could catch it.’” He offers her a beer; she declines. He tells her about Shoeless Joe Jackson, the great hitter for the Black Sox, and Eddie Gaedel, the midget who made one plate appearance for the St. Louis Browns. “Blue Corduroy responded by saying she would have the beer I had offered before, and I would hate to think now that she accepted just to make me shut up.”

The ushers are passing out roses to women in the stands, and she gets one: “‘Two days here, it’s time I got one,’ she felt she had to explain to me, and said it in a way that made me feel she had been roseless for ever so long.” The Dodgers prevail, and the loss inspires Algren to poetry: “It was a day that began with rain, that bloomed brightly with base hits and roses and came at last to a melancholy end. But not for the woman in blue corduroy who got the rose so long overdue.”

In the final, fatal Game Six, the Dodgers plate six runs in the fourth, and “a dark eyed woman behind me began calling on God, ‘Let it rain. Let it rain.’” When that doesn’t work, she calls on White Sox manager Al Lopez to put Honey Romano in the game because he’s hitting .625. Algren knows Romano is hitting below .300, but he won’t argue with an Italian: “As a book reviewer with barely enough clout to squeeze into the upper right-field stands I didn’t feel qualified to dispute the point, and… I am not the kid to buck the Mafia.”

The women help Algren string readers from hope to heartbreak without writing play-by-play. By not knowing or not caring about baseball, they transcend the game’s concerns, and that’s precisely the use for women—as a deviant and inferior other—that Simone de Beauvoir deplores in “The Second Sex.”

Feminists wonder why Beauvoir accepted in Algren the very tools of oppression she exposed in mankind—research? tolerance? love? But in the 1940s, Beauvoir considered hostility as slavish as docility—“The praying mantis is the antithesis of the harem girl, but both depend on the male”—and she saw autonomy as the answer to oppression. When Algren grew bitter he mocked her, but when he was brilliant he gave her good advice—to use racial discrimination in America as a model for her book on women.

They met in 1947, when Beauvoir was drafting “The Second Sex” and Algren was drafting “The Man with the Golden Arm.” Hers became a foundational text of feminism. His won the first National Book Award. The gossip about their first date, often repeated, subverts recognition of another important Chicago writer. Algren may have been her guide, but her vision is her own, and her vision of Chicago is as apt as anything by Algren or Richard Wright or Carl Sandburg. In her novel, “The Mandarins,” Beauvoir describes a fictional cab ride from the Palmer House to 1523 West Wabansia to meet Algren for the first time. It was February:

“There were a great many streets and all of them looked alike; they were bordered by tired frame houses and scrubby little yards that tried to look like suburban gardens. We also went down straight bleak avenues; everywhere, it was cold…. The cab crossed bridges and tracks, passed by warehouses, went down streets in which all the shops were Italian. It finally stopped at the corner of an alley that smelled of burned paper, damp earth, poverty; the driver pointed to a wooden porch projecting from a brick wall. ‘That’s it.’ I walked alongside a fence. To my left, a saloon decorated with a red, unlit neon sign: ‘Schlitz’; to the right, on a large billboard, the ideal American family smilingly sniffing a bowl of hot cereal. A garbage pail was smoking at the foot of a wooden stairway. I climbed the stairs. On the porch, I found a windowed door on the inside of which hung a yellow shade; that was probably it. But suddenly I felt nervous. Wealth always has something public about it, but the life of the poor is an intimate thing; it somehow seemed indiscreet to knock at that windowpane. Hesitantly, I looked at the row of brick walls to which other stairways and other gray porches were monotonously tacked. Above the rooftops, I saw an immense red-and-white cylinder: a gas tank; at my feet, in the center of a naked square of earth, stood a black tree, and at its foot a little toy windmill with blue sails. In the distance, a train passed; the porch trembled. I knocked and there appeared at the door a rather tall, rather young man, his chest stiffened by a leather jacket. He looked at me in surprise.

‘You found the house?’

‘So it seems.’”

In “America, Day by Day,” Beauvoir describes Maxwell Street, West Madison Street, North Clark Street, the lakefront, the stockyards, the police lineup, with as sharp an eye for boss and worker, black and white, as Algren or Sandburg, but where they reach for a metaphor she unsheathes a shimmering thought. She notices in 1947 that America runs on optimism, for example, and that optimism leads us to blame our poor for their poverty. Anyone can succeed here, we must believe, so something must be wrong with those who don’t.

Her tour includes a White Sox game: “Vacantly, I watched the strangely dressed players who were running about on the aggressively green grass.”

Maybe Beauvoir killed the beast. That’s one theory that emerges when panelists ponder Algren’s collapse. Beauvoir was tolerant but would not be tamed. In 1951 he wrote to her, “The disappointment I felt three years ago, when I began to realize that your life belonged to Paris and to Sartre, is an old one now, and it’s become blunted by time. What I have tried to do since is take my life back from you.” But in 1960, granted a passport at last, he sailed to Paris. And came home alone.

Or it might have been the gambling. It might have been the critics. It might have been the McCarthy era that did Algren in. Unable to publish his views or muzzle them, Algren resorted to satire and was dismissed as a clown. So goes another theory.

There’s also the view, espoused by Algren’s friend Art Shay, that he just lost his stuff. “He was not a good caretaker of his talent,” Shay said at the Columbia College tribute last month. “He dried up to a certain extent.”

For a time, Algren had outperformed the best American writers. He wrote “The Neon Wilderness,” “The Man with the Golden Arm” and “Chicago, City on the Make” in the span of five years, and then he slipped into a decline so prolonged—thirty years, some reckon—that a reviewer criticized his biographer, Bettina Drew, for subjecting readers to it. But it’s hard to figure Algren without the decline, which dropped him through the membrane between the city and its literature, preserving him as a character in the myth of Chicago that he had helped to craft—a nobody, a ghost, the ninth man out.

In 1975, Algren left Chicago for good. Chicago Tribune columnist Rick Soll attended his moving sale in the third-floor flat at 1958 West Evergreen. His neighbors, Soll notices, don’t know who Algren is, but the press has noted his departure. “For the first time in my life, now that I’m leaving, Chicago is finally saying some nice things about me,” Algren told Soll. “You know, the kind of praise I wouldn’t be getting unless I had just died.”

Algren died six years later in New York. Long Island took his body. The Ohio State University took his archives. The City of Big Shoulders mostly shrugged him off. The famous symbol of indifference is Evergreen Avenue: the city changed its name to Nelson Algren Avenue, and when residents complained, changed it back. But over the years Algren’s light has flickered in the neon wilderness: awards were named for him, a fountain dedicated, a committee formed, a play staged. Mike Royko and Studs Terkel championed his work. His books, all out of print when he died, are all back in print, with two new volumes out this year. There are signs Chicago sees itself increasingly through Algren’s eyes as the city of hope (Obama) and the hustler (Blagojevich). It’s not just the cross of St. Columbanus that gazes down upon the gray streets anymore, but the uncompromising writer who demands, “What have you done for the nobodies nobody knows?”

“I submit that literature is made upon any occasion,” Algren wrote, “that a challenge is put to the legal apparatus by conscience in touch with humanity.”

In 1986, Simone de Beauvoir, a conscience in touch with humanity, was buried beside Jean-Paul Sartre, wearing Nelson Algren’s ring. In 2005, the White Sox got their rings, touching the conscience of the vast humanity sprawled south of Roosevelt Road. And if you want to know where Nelson Algren is during all these soirees held in his honor, consider that hope still springs from the South Side, reaching all the way to the White House sometimes, and not a day goes by at 35th and Shields that Cicotte doesn’t strike out Ruth.

“The crush of the mob swept police, horses and myself onto the field, and I scampered into the centerfield bleachers,” echoes a voice from the silver-colored yesterday. “I’ve been in the centerfield bleachers ever since.”