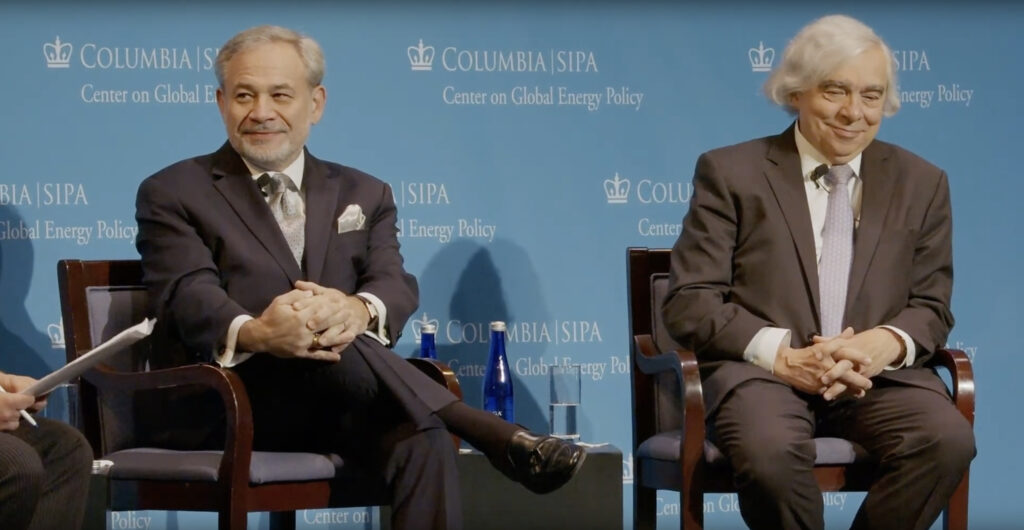

Dan Brouillette (left) was President Trump’s energy secretary from 2019-2021. Ernest Moniz served under President Obama from 2013-2017. The two men shared a stage Oct. 12, 2022 at Columbia University’s Global Energy Summit. COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY | SIPA

Two former U.S. energy secretaries agreed on almost everything at a joint appearance Wednesday, including the opportunity to tell Germany ‘I told you so.’

Trump’s second energy secretary, Dan Brouillette, brought up Germany right off the bat at Columbia University’s Global Energy Summit in New York.

“We felt very strongly that Germany had become too dependent on one source of gas supplier—i.e., Russia. Gazprom,” said Brouillette, who held several lobbying jobs and congressional staff jobs before helming the Energy Dept. from 2019-21.

“We tried to make the point. They disagreed with us, and that was their right to do so. But today I’m watching Germany take some very dramatic steps to broaden out their energy supply, if you will, to diversify their portfolio overall.”

Ernest Moniz, the Nobel-Prize winning physicist who served as President Obama’s second energy secretary from 2013-2017, made sure Brouillette understood that Germany had heard that warning before.

“Along the lines of what Dan said, in fact, the rather stern lectures to our German colleagues about the bad hygiene of their energy security situation predated your administration,” Moniz said.

“I can recall the heavy perspiration of the German ambassador in my office, for example. So this has been a consistent theme across administrations that the German situation just wasn’t healthy, and unfortunately it’s come back to bite them and all of us frankly.”

Germany famously shut down its nuclear reactors after the 2011 Fukushima Disaster and invested heavily in renewables, which helped make solar-photovoltaic the cheapest energy technology for the world. It also began shuttering coal plants. But Germany counted on Russian natural gas as a bridge fuel for the transition. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, Germany and the rest of Europe have seen that supply squeezed, threatened, and sabotaged. Energy prices have soared globally, but particularly in Europe.

According to Moniz, Germany did an excellent job envisioning a clean-energy economy in 2050, but a poor job managing the 30-year transition to arrive there, which—he agreed with Brouillette—will require traditional fuels, such as fossil fuels and nuclear.

Trump’s lobbyist and Obama’s physicist agreed on most things: on the need for a diverse portfolio of energy sources, on the recognition that energy security and environmental security go hand in hand, on the collective responsibility among nations to manage energy security, and on almost everything else:

Brouillette: “We don’t disagree as much as you might think. Ernie was instrumental in creating the export of LNG (liquified natural gas) and creating those policies that allowed us to produce more here in the United States. It created a global market for U.S. natural gas.”

Moniz: “It’s true that we did most of the approval of licenses for export.”

But then Brouillette crossed a bridge too far:

Brouillette: “As we think about transition I don’t think we should think about it as one fuel source completely replacing the other.

“If you think about human nature, if you think about humanity from whatever time period that you want, the transition has never been from one type of fuel to another…. The transition, if you will, has always been from less energy to more energy. That’s been the transition of humankind, that’s where we need to continue to go, and yes within the portfolio sometimes things will change. We’ll use less coal than we did, say, 50 years ago, as part of the portfolio, but it will always be additive. We will always be adding more energy, because that’s what society needs. It’s what economies grow on. It’s what populations are going to demand.”

Moniz: “I’m sorry. I’m going to have to now finally disagree with my colleague. The additive comment has got to be parsed by level of development of economies. So the industrialized world, yeah, we may have some increase in energy use, but not material, the way that you were describing, all the new fuels being additive.

“And in fact, that’s another reason why in the industrialized world we are facing a more difficult challenge in the sense that there’s going to have to be a lot of displacement of incumbent fuels and technologies going forward.”

Read More:

Did Europe Move To Renewables Too Fast, Too Slow Or Just Right?